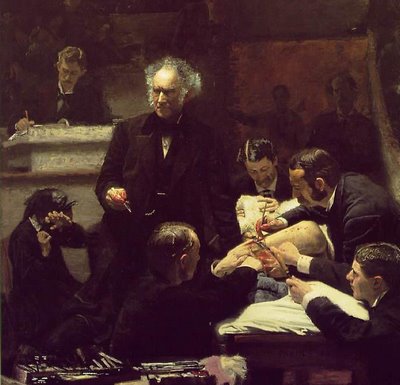

"The Gross Clinic", by Thomas Eakins

By Aussigirl

Recently I posted articles about two paintings that sold for astronomical amounts of money, one by Klimt and the other by Picasso. I wouldn't have put either painting on my wall, because to me their gravest fault was that they lacked emotion -- the Klimt was merely gaudy, and the Picasso -- well, it was ugly, pointless, and if someone named Pisacco had painted it, it would have been thrown onto the trash heap.

This painting, on the other hand, as well as being masterfully crafted, beautifully lit, and all the elements wonderfully positioned, is full of emotion -- the varying emotions of the professor, the surgeons, the man taking notes, and the frightened, weeping woman in the background, probably the mother of the patient.

The Gross Clinic - Thomas Eakins - Thomas Jefferson University - New York Times

Eakins Masterwork Is to Be Sold to Museums

By CAROL VOGEL

Published: November 11, 2006

In 1878 the alumni of Thomas Jefferson University, a medical school in Philadelphia, scraped together $200 so the institution could buy a painting depicting a revered professor, Dr. Samuel D. Gross, performing a gory operation on a man’s thigh. Today that work, “The Gross Clinic,” by Thomas Eakins, is widely acknowledged as one of the greatest canvases of American art.

Yesterday the university’s board voted to sell its prized 1875 painting for $68 million to the National Gallery of Art in Washington and the new Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, founded by the Wal-Mart heiress Alice L. Walton and under construction in Bentonville, Ark. That sum is a record for an artwork created in the United States before World War II.

Mindful of potential objections from residents of Philadelphia, Eakins’s lifelong home, the university has given local museums and government institutions 45 days to match the offer.

Anne d’Harnoncourt, director of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, said she would immediately explore the possibility, perhaps in tandem with the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art. “It’s a painting that really belongs in Philadelphia — his presence still resonates here,” she said of Eakins’s masterwork. “There may be a way we could band together to make it happen.” [...]

The work is one of the largest (roughly 8 by 6½ feet) and most complex compositions Eakins painted. Depicted holding a scalpel in the vast amphitheater of the Jefferson Medical College, Dr. Gross looks out at his associates, assistants and students, addressing them as he removes a piece of dead bone from the thigh of a patient suffering from osteomyelitis, a common ailment of the time.

Alongside him, five doctors attend to the patient, whose bloody thigh is visible to the viewer. Eakins casts a strong light on Dr. Gross’s brow and scalpel.

“He is both doer and thinker, as the dual emphasis on head and hand testifies,” writes John Wilmerding, a professor of art history at Princeton University and a National Gallery trustee, in an essay called “The Tensions of Biography and Art in Thomas Eakins.”

The finely detailed canvas articulates the doctor’s bushy, furrowed brow, bloody hands and silver hair, suggesting his knowledge and hands-on experience.

Often compared to Rembrandt’s paintings of anatomy lessons, “The Gross Clinic” was considered revolutionary for its time. Never before in this country, art historians say, had an artist painted an actual operation in progress with medical instruments and blood in full view.

When the painting was exhibited in 2002 in an Eakins retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Michael Kimmelman, the chief art critic for The New York Times, called it “hands down, the finest 19th-century American painting.”

But throughout its history, the graphic details have given viewers pause. In 1879, while it was entered in the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, the canvas was rejected by the art committee and relegated to a display of medical instruments and hospital equipment.

At the time, a critic for The New York Daily Tribune said it was “one of the most powerful, horrible, yet fascinating pictures that has been painted anywhere in this century — a match for David’s ‘Death of Marat,’ or for Gericault’s ‘Raft of the Medusa.’ ”

“But the more one praises it, the more one must condemn its admission to a gallery where men and women of weak nerves must be compelled to look at it,” the writer said. “For not to look at it is impossible.” [....]

3 Comments:

The other arts suffered too after the introduction of relativism.

"Modern" art and music?

When will history come to realize most of it is garbage?

The sale of this treasure by officials at my alma mater is tragic

Please help to prevent the loss of this painting by making a contribution to the fund to keep it in Philadelphia:

http://www.philamuseum.org/giving/509-398.html

Thanks.

Post a Comment

<< Home